In 2010, a group of wine producers in Chile set up an unprecedented association called Vigno dedicated to just one variety of wine from just one area of Chile. Why? Because they thought that some really special wines could be made from the old and largely unappreciated Carignan vines in a remote, dry area of Maule.

Fast forward nine years to an international Carignan seminar in the Chilean capital of Santiago. It was like the who’s who of Chilean wine: just about everybody who is anybody was there. The disinterest many of Chile’s wine producers once showed towards Carignan has long since vanished and even Chile’s largest companies, like Concha y Toro, have now jumped on the Vigno bandwagon.

Carignan exports from Chile

According to wine consultant Fernando Almeda, while volumes are still low – a total of 22,000 nine-litre cases of Carignan were exported from Chile in 2018 – it now ranks 9th among Chile’s varieties in terms of average value at US$73.50 per nine-litre case in 2018. Compare that to an average export price to the US of just US$29.20 per case for Cabernet Sauvignon and you can see why wine companies are sitting up and taking notice.

So just what is so special about this wine? Well first off, although there are 52,000 hectares of Carignan planted around the world, mostly it is used to add a bit of acidity, colour and tannin to blends. There are only a very few places where producers are taking pride in making Carignan as a single variety wine in its own right, most notably Sardinia in Italy, Priorat in Spain, Languedoc in France, California in the US and Maule in Chile. What they all have in common is that the grapes are from old, low-yielding vines planted in poor soils in places that have the warm, dry climate needed to fully ripen them.

Chile’s producers believe that old-vine Carignan from Maule is quite unique in its own right and different to the wines being made in the other regions. A tasting of Carignan wines from the different regions during the seminar certainly seemed to back their claim. Two parallel research projects by Universidad de Chile and Universidad de Talca have been looking into whether this is really the case and, if so, why.

What makes Chilean Carignan different?

Dr. Álvaro Peña explained that the Universidad de Chile research team had found that the Carignan from Maule had a greater level of monomeric and oligomeric tannins than the wines they tested from other regions, which means those wines have more colour, more bitterness and greater length. They were also found to have a lower pH and more tartaric acidity, giving the drinker a perception of greater acidity and more persistence. The aroma profile of Chilean Carignan varies according to area and ripeness level but overall their volatile components tend to lend the wines fruity aromas, like plums, cherries and green apples, as well as floral aromas like violets and roses, a profile quite different to the wines from other countries that were tested.

The researchers from Universidad de Talca have studied the different climate and soil factors at 24 different locations at Maule to try to identify what makes Maule old-vine Carignan so special. They found two particular factors that set Maule apart from other Carignan areas. The first is the significant drop in temperature at night, which, by slowing ripening, helps with acidity retention and phenolic development. Second is the poor nature of the soils, which have a very low pH and are low in potassium. The grapes therefore also have a very low pH and are so low in potassium it is difficult to vinify them.

The future of Carignan in Chile: just old vines or new plantings?

So the question has to be asked: what is the future for this variety in Chile? Will it remain a niche product made from the current very limited stock (707 hectares) of old vines in the dry inland area of Maule or will new plantings take off, perhaps even in other areas of Chile? Can Maule’s Carignan success be replicated elsewhere?

Fernando Almeda strikes a note of caution. Carignan is gaining a name for itself in a few niche markets but is largely unknown to most wine consumers around the world – it’s a much safer investment to plant a well-known variety like Cabernet Sauvignon. Also, the manual labour and low yields that are inherent to the old-vine Carignan from Maule make it expensive to produce, meaning it can’t be sold at the low price point needed to make it a success in the mass market.

However, others are more upbeat. Vigno President Julio Bouchon says that Bouchon Family Wines recently planted a vineyard of Carignan in Maule under the same conditions as the old vineyards: dry-farmed and trained into a bush form. He says that this will enable them to compare the results of old and new vines and, of course, today’s new vines are tomorrow’s old ones.

Well-known winemaker Marcelo Retamal has planted Carignan in granitic soils at a dizzying altitude of 2,200 metres above sea level in the Elqui Valley in northern Chile. While the first vintage had ferocious acidity to start with, he says that after several years of ageing, it’s now a lovely wine. Marcelo feels that while the major international varieties like Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot may be the bread and butter of large wine companies, smaller producers may do well to differentiate themselves by planting alternative varieties like Carignan. He certainly sees a future for the variety beyond the borders of Maule.

Potential for pepping up blends

In the meantime, there are some experts in Chile who believe the future of Carignan is much bigger than the current small-scale plantings. Dr. Peña cites producers in Bordeaux who think that the warmer conditions resulting from climate change may cause the traditional Bordeaux varieties like Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot to become overripe and low in acidity, making for flabby wines with jammy flavours and reduced ageing potential. In recent years, producers have been trialling a whole range of different grape varieties that cope with warmer climatic conditions, including Carignan. These wines could be used to add much-needed acidity to the wines in future, just as they have done for many years in the Southern Rhone and Languedoc.

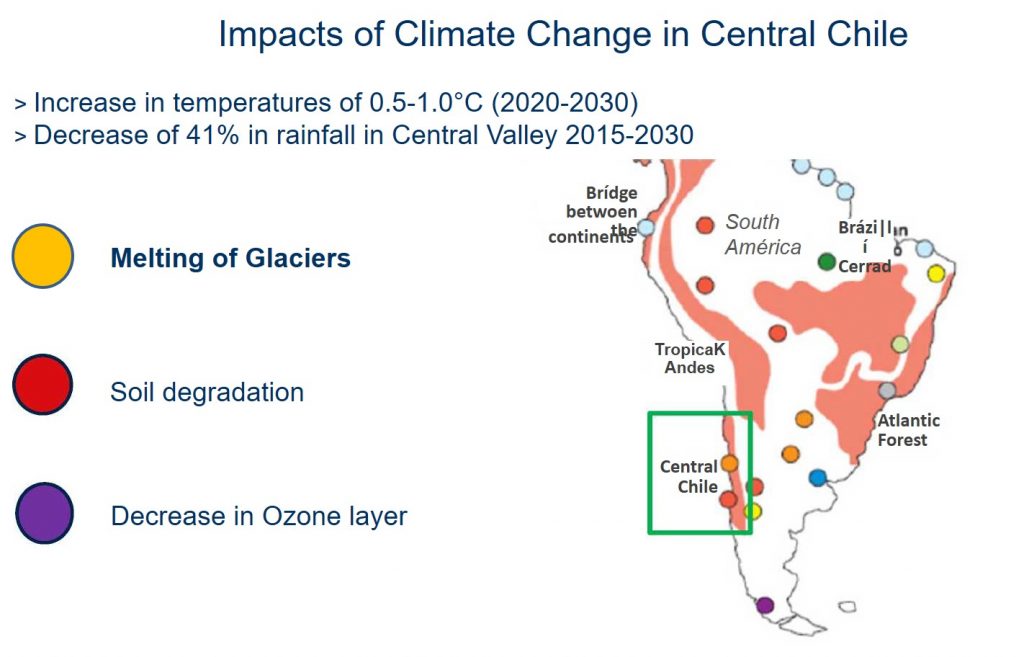

Dr. Peña argues that producers in Chile’s Central Valley, which is extensively planted with the Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot and Carmenère, would do well to follow the example of Bordeaux. Climate change predictions suggest that temperatures in this area could increase by up to 1°C by 2030, while rainfall may decrease by 41% in the period 2015-2030, so it is reasonable to assume that the grapes may also have problems with acidity and jammy flavours in future. Perhaps this is a good moment for producers to consider planting Carignan or other heat- and drought-resistant varieties in the region to pep up the wine blends of the future. This idea has won support from Pablo Morandé senior, a highly-respected figure in Chile’s wine industry.

Only time will tell whether Chilean Carignan will remain a niche product or become a major blending partner but one thing is for certain: this once-maligned variety is now being appreciated like never before. And perhaps the greatest lesson of all is that when a group of producers work together collaboratively towards a common goal, as is the case with Vigno, the results can be amazing.

Check out Our guide to Chilean Carignan

Learn more about Carignan over on 80 Harvests where we interviewed and profiled several producers in Maule:

- Coming of Age: Chile’s Carignan movement & Vigno

- Maule Fast Facts & Terroir Essentials

- Carignan Profile

- What is VIGNO?

- Maule and the Carignan boom

- The diversity of Maule terroir

- Wine Drinking with Wine Makers: Arnaud Hereu and Andres Sanchez