With over 700 different grape varieties planted, the experimental vineyard block in Mendoza’s National Agriculture Technology Institute (INTA) is an absolute gold mine for vines. There are few places in the world with such a diverse range of grape varieties (this is the third largest collection in the Americas) and INTA boasts not only diverse international varieties but also some pre-phylloxera genetic material that has been lost in the Old World and an exciting collection of native Criolla varieties.

“This is a really hard vineyard to maintain,” Jorge Prieto, one of the vineyard technicians in charge, tells it like it is. “With 700 varieties [usually with five plants each] all planted next to each other it is not easy. However, this is the most important genetic bank we have in Argentina. This vineyard is about the conservation of germplasm.”

The vineyard, which was first planted in 1949, not only has a diverse mix of international varieties, but it also has many varieties stowed away that are unregistered anywhere in the world. This is especially the case with the native Criolla varieties.

Deciphering the future for Criolla wines

While INTA’s work spans far beyond the 54 Criolla varieties they have planted, I was in particular interested to see what research they are working on in the diverse web of Criolla grape varieties in Argentina and South America today.

(Get to grips with the definition of Criolla varieties here!)

A dedicated team of seven have been working on identifying, categorizing and vinifying some of the first grape varieties to be planted in South America and their subsequent offspring. Since 2011, the team have been vinifying the 54 Criolla varieties they have planted and have been on the hunt for more unidentified Criolla vines around the country. Over a third of Mendoza’s vineyards are planted with Criolla varieties, and this year the team is adding 10 more Criolla discoveries to the garden. Undoubtedly many more will follow as the project progresses.

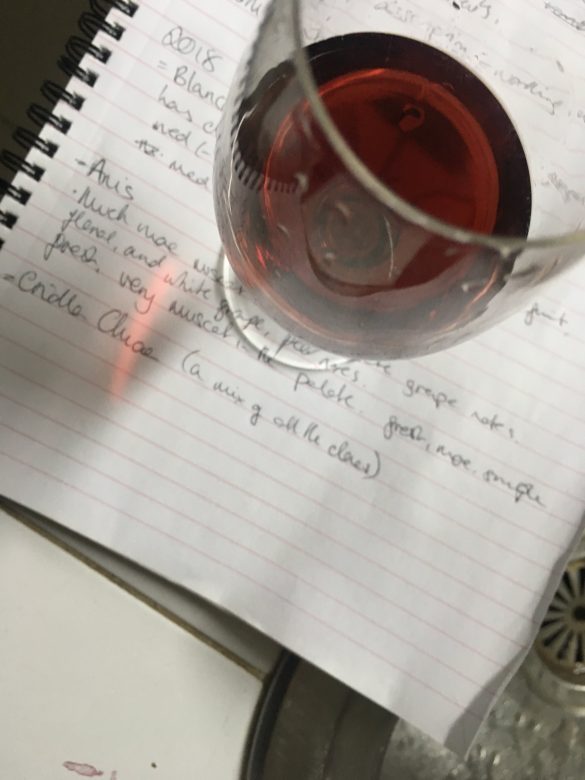

Of those varieties currently in the experimental vine-garden, each year they vinify minuscule productions (in some cases only 10 bottles) of some of these grape varieties in order to test out their viability for wine production and oenological worth. The wines are made simply with a neutral yeast and a standardised winemaking procedure with zero additions or corrections in winemaking.

“We are looking at how the grapes show their aromatic expression and differentiation in aromas,” explains resident winemaker Santiago Sari, “as well as persistence in the palate and good natural acidity. We produce these wines as a control experiment to see how they stand on their own – before any winemaking choices as such.”

When a grape variety passes the test one year, it goes on to be vinified for three more years before the team begins experimenting with different winemaking techniques to see how it could be developed. Successful varieties will be propagated to grow the population (in some cases these are the only plants still in existence as far as they know) and then shared back into the greater winemaking world of Argentina.

The common Criolla varieties of Criolla Chica, Torrontés and Moscatel Rosado continue to show great oenological potential, but there have also been some surprises in the experiment. “Blanca Oval is one of the more interesting varieties that we have discovered so far,” says Gustavo Aliquo, another of the vineyard technicians. “And there’s a very rare grape, currently called Criolla Number 1, which has a lot more colour and structure than a Criolla Grande. We discovered that Criolla Number 1 is a cross between Criolla Grande and Malbec. And it has great winemaking potential!”

How many Criolla varieties are out there?

The 54 varieties currently being hosted in INTA’s vine garden could just be the tip of the iceberg. “Every year we are discovering other Criolla varieties that have been forgotten about and practically disappeared,” says Elena Palazzo, who is in charge of managing the producers that INTA works with. “There are many vineyards in Mendoza which haven’t been modernised and have these ancient varieties between vine rows.”

The team regularly visits vineyards together and walk through the rows trying to identify unique varieties which they haven’t seen before. “You need to visit between November and March when the vine has leaves,” explains Rocio Torres, who takes care of the genetic studies for the project. “Then we can take a sample leaf from the vine and study the DNA.”

It is through this DNA testing that they have identified over 18 Criolla varieties that were previously unknown – including several of which they are vinifying this year. There are, however, undoubtedly many more hidden deep in the old vines across not only Argentina’s wine regions but those of Chile, Peru and Bolivia.

The challenge will be getting there on time – and proving the wines are worth paying for and making – before the enormous wealth of Criolla varieties in South America is abandoned.