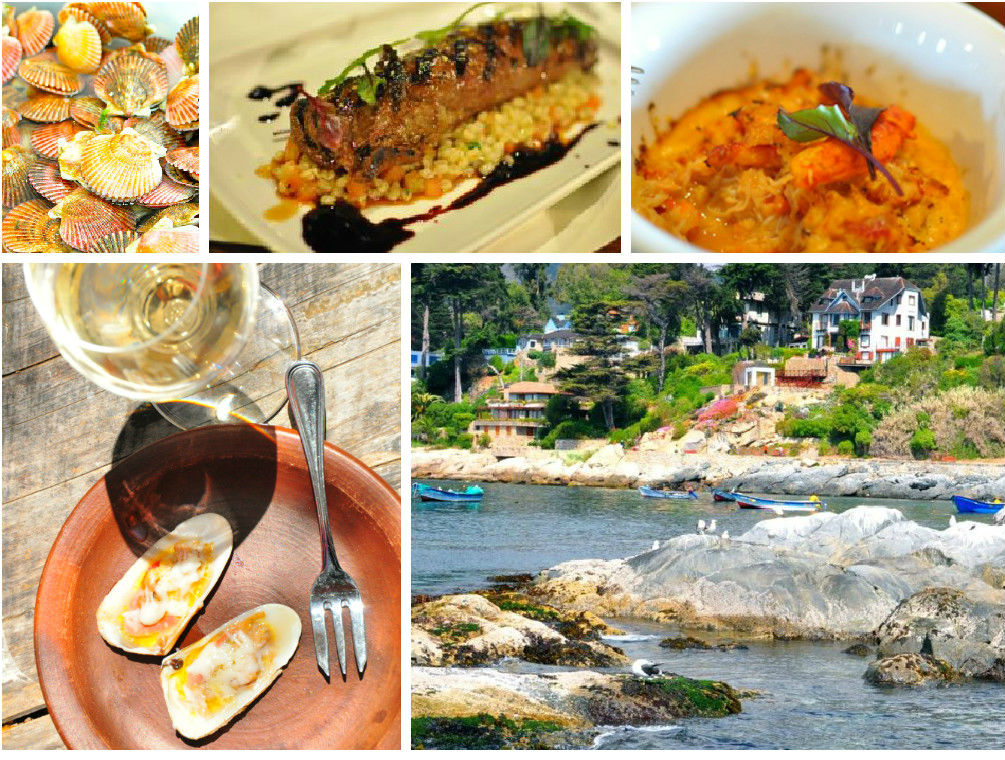

Chilean oood is driven by local identity, tradition and a wealth of native ingredients that are found along its striking 4,630km length. Characterized by the rugged Pacific coast and dizzying heights of the Andes mountains stretching almost the entire enviable length of the country, Chile’s topography extends over 29° of latitude ranging between the tropics, arid deserts, salt flats, fertile hillsides and valleys, deep forests, jagged glaciers and fjords, snowcapped mountains and volcanoes. Although all ingredients are local, Chile’s key gastronomical and viticultural asset is its diversity.

Moving in from the coastal mountain range the country morphs into warm flat plains, breeze brushed foothills and the rugged start to the Andes. Naturally the cuisine shifts focus onto land dwellers and Campesino (rural) cooking dominates. The simple Huaso Asado (Chilean cowboy’s BBQ) with grilled meats like pork, beef and lamb are an ideal partner to the bigger reds from the Central valleys. The Asado tradition of hours spent around the fire warrants an equally time-absorbing wine.

Another favourite of the cowboy culture and prepared all over Chile is the hearty stew. Usually with a base of root vegetables, coriander and full flavoured meats like cow tongue, it pairs well with what really was a Campesino’s wine of years past: Carignan.

In the Southern regions of Maule, Itata and Bío Bío some gnarly trunked, old bush vines had been forgotten by the wine world, until recently. Old vine Carignan from Maule is a muddle of rich cassis, mulberry and wet earth with a refreshing acidity. “Carignan from Maule is concentrated but not necessarily rustic,” says owner of Santiago wine bar Bocanariz, Katherine Hidalgo. “It has a countryside flavour but it can be super elegant.”

País too is a rediscovery. Once the most planted variety in Chile, it was later dismissed as table wine to make way for noble varieties, although now the old vines – some up to 350 years old – are producing unique wines. More rustic than Carignan, País has dark fruit and drying tannins with attractive floral and citrus notes.

Like anywhere, stews in Chile are made big. They are inherently for sharing. One treasured national dish is Estofada de San Juan, a stew comprising dried and smoked meats with acid cherries and always eaten on 24 June, National Indigenous People’s Day. As part of the necessity of the day, the native Mapuche tribe had a rich culinary culture preserving foods – still echoed in contemporary cuisine.

One spectacular indigenous dish is Curanto, coming from the lost-in-time Chiloe archipelago. Villagers tie a stilted house onto a platform and, with oxen, drag it to a new location in an annual ‘Minga’ ceremony. This century-old tradition is followed by a Curanto cooked for the entire village: a large hole filled with hot stones where layer upon layer of shellfish, meat, potatoes, vegetables and dumplings are covered by native Nalca leaves and cooked underground.

Time-conscious, less romantic chefs replicate it in a pressure cooker.

The greatest Mapuche inheritance though is Merkén. This heady combination of smoked chilli peppers, coriander seed and sea salt is used to add flavour to many dishes in Chile, which unlike its namesake actually features little spice in typical dishes.

Carménère’s juicy fruit and appealing spice, is a perfect pair for not just Mapuche dishes though. “Carménère is a great variety with a medium body so you can pair it up or down, with lighter or heavier dishes,” says Marcelo Pino, Best Chilean Sommelier 2015. “It’s a very versatile wine.”

Cabernet Sauvignon is equally as versatile in Chilean food pairings. “The commercial style of Chilean wines makes them very easy to drink and pair,” comments sommelier Martin Mantegini, “even Cabernet Sauvignon.” The most acclaimed Chilean Cab is arguably from the rocky Andean terrains of Alto Maipo, reaching up to 800m altitude and producing deep, layered and lush wines with rich cassis, red fruits, chocolate and elegant herbal aromas.

The softer Merlots and jammier, medium bodied reds of the Central Valley are often paired with the nation’s No.1 comfort food, Pastel de Choclo: a casserole with a base of ‘pino’ (minced beef, chicken, raisins, boiled eggs and onions), topped with a corn crust. The creamy corn used in many Chilean kitchens, especially for Humitas (wrapped with onion and basil in corn husks) is also a great pairing for buttery oaked Chardonnay.

This abundance and diversity in Chilean food and wine makes the country mouthwateringly good to discover.