BIRA is the boutique winery and artisanal wine production of Federico Isgró and Santiago Bernasconi focusing on Sangiovese based red blends from old vines in the Uco Valley in Mendoza. Supple, sumptuous wines that celebrate the Italian heritage and old vines in Argentina.

"argentina"

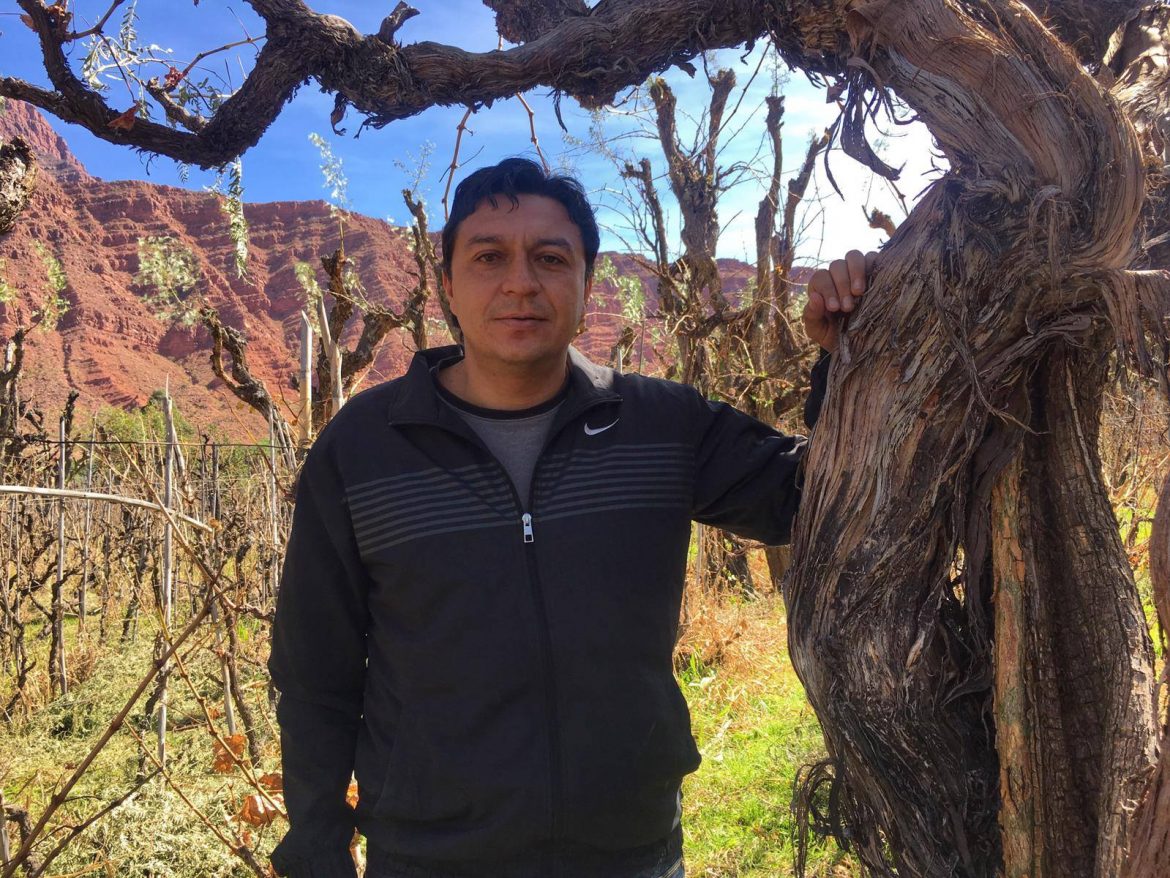

Jaime Rivera is a fourth-generation vigneron in Bolivia’s Cinti Valley where he tends old Criolla vines of over 200 years old which are trained around molle and chañar trees. In this interview, Amanda Barnes asks Jaime Rivera about some of the secrets of the Cinti Valley including how the native grape variety of Vischoqueña arrived. They discuss traditional viticulture in the Cinti Valleys, and how he has learnt traditions passed on from his ancestors which he continues today with Bodegas Cepa de Oro.

So Jaime, how old is this vineyard that we are stood in?

This vineyard has plants that are over 100, in fact over 200 years old. Where we are there are the varieties of Negra Criolla, Vischoqueña and Moscatel.

Excellent, and these are the most authentic and oldest varieties, and original here in the region. Because some were born here in the region. Please tell us about the story of the Vischoqueña grape.

These regions are the most typical of the Cinti Valley wine region. The Vischoquenña, Moscatel and Negra Criolla, and the first to arrive were Moscatel and Negra Criolla. Which were brought here in the colonial era by the Spanish. The story of Vischoqueña says that in the region of Vischoca, here by the Rio Grande, they were bringing some vines (we don’t know what vines exactly) and the cart overturned with all the vines and the spilled all done the river. And on the river banks, these grapes started to grow, and because it was in the Vischoca region the grapes were named Vischoqueña, and it was a very productive grape, a delicious grape. And so here in the region of the Cinti Valleys we all started planting this grape too, especially near the Rio Grande (a river which runs down south here).

How interesting! And the other thing that is really interesting here is the way in which the vines grow – because here we have a vine and a tree. So the ‘tutor’ is the tree, and the grapes grow around it. Can you tell me a bit about the benefits of growing grapes in this way, why is it good for the vine to have this protection from the tree?

The old way of planting, the way my grandparents did for example, they say has the benefit of protecting the vineyard from hail, and frosts. By being in the tree, the grapes which are growing up here on the pergola (these trees are chañar and molle) are protected by both the hail and the frost. Because before we didn’t have hail nets, and it’s impossible to use hail nets with a formation like this. So our ancestors planted the vineyards like this for protection. The vines are also more productive when they are grown like this. This is a parral (pergola).

And how much can a plant growing on a tree like this produce?

Well it depends, on whether it is a molle or chañar tree. But it is around 10 kg per plant.

Great, and is it easy to harvest?

It’s very difficult! You have to go up with ladders to reach the grapes, and also to prune. You have to do everything by hand too.

Interesting. And here behind us we can see that Cinti is really in a valley between mountains…

Yes, exactly. And that’s what’s great about this valley. We call it the Coloured Canyon of Cinti Valley. It has a very unique climate, and thank God it is very suitable for grape growing because of these tall mountains. We have very hot days and very cool nights, which means the grapes arrive to an excellent maturity. We easily reach a minimum of 13% abv, and can reach 14 or 15% too. This is a great advantage we have here in the region, the grapes get to their full maturity.

And the wines are delicious!

Yes, I think so no? They have their characteristic of the region.

Read more on Bolivian wine:

“When you are born with a family name like mine, it can put you off being in the wine industry…” ruminates Gabriela Furlotti, the great-granddaughter of Angel Furlotti, who became one of the 20th century’s most prolific grape growers and wine producers in Mendoza, establishing Bodega Furlotti in 1914. The winery reached peak production in the 50s and the Furlotti family was one of the world’s largest vineyard owners at the time. Furlotti became a household name in Mendoza, as did their ‘Vino Leon’ wine, which was a popular fixture on most family dinner tables. “It certainly adds a lot of pressure to have the Furlotti name if you want to do anything in wine.”

Furlotti’s family history can help trace Argentina’s wine industry boom for over a century, as well as its demise at the turn of this century. Her decision in the early 2000s to rekindle the family story in wine, with a much narrower focus, also shows the changing vision of Argentine wine producers today. But before understanding why small is sometimes more beautiful, we have to put into context the century proceeding ours.

Furlotti’s family history can help trace Argentina’s wine industry boom for over a century, as well as its demise at the turn of this century. Her decision in the early 2000s to rekindle the family story in wine, with a much narrower focus, also shows the changing vision of Argentine wine producers today. But before understanding why small is sometimes more beautiful, we have to put into context the century proceeding ours.

Fresh off a boat and into the vineyard:

Angel Furlotti establishes roots in Mendoza as the wine industry takes seed

Angel Furlotti arrived to Argentina in 1888, with barely a dime in his pocket, from a small village outside Parma, in a period of mass European immigration. Over 7 million European immigrants arrived to Argentina between 1847 and 1939, almost doubling the population every 20 years, and mainly comprised of Italians, Spaniards, Germans and French – each of whom brought their own vine growing knowledge.

A government-led incentive offered free train rides from the port of Buenos Aires to the western mountain towns, in order to get people settling in Cuyo and ‘conquering the desert’ with viticulture and agriculture.

Recently arrived immigrants were invited to stay in convents until they had saved enough money to construct their own houses, and the contratista employment structure at the time allowed new immigrants to get a foothold in the economy. There were two models of contratista employment: a contratista for an established vineyard, who was only given a small salary for working the land but received 18% or 20% of the profits; and a contratista de plantacion, who was loaned virgin territory to plant a new vineyard, and received 100% of the profits.

“If they were hard workers and knew how to produce, immigrants could quickly get enough money to buy their own land – it’s how the industry grew,” explains Gabriela, whose great-grandfather started working as a contratista de plantacion in the early 1890s. By 1914, Angel Furlotti had accumulated enough land and vineyards to construct his own winery. “Land was cheap and if you worked hard it was possible to make a name for yourself back then.”

The influx of immigrants combined with the new railway (completed in 1883), which connected Mendoza to the market in Buenos Aires, meant that wine production could grow at an unprecedented rate. Before the railway, in 1883, there were just 2,788 hectares of vines planted in Mendoza, and within 20 years there were over 20,000 hectares (c. 1902) and by 1914 over 70,000.

The ‘American dream’ was well and truly accessible for those willing to work hard enough to achieve it, and in this period the founding fathers of Argentina’s modern wine industry all accrued significant land for vineyards and were producing wines at a rapid rate. Many of these original families are still major players in the industry today (Graffigna, Toso, Benegas, Suter, López, Pulenta, Arizu).

In the case of the Furlotti family, Angel Furlotti and his children went on to become Argentina’s largest vineyard owning family, and by the 1950s, the Furlotti family had 10 vineyards amounting to over 2,000 hectares, spread across Maipu, Luján and the Uco Valley, including today’s renowned sub-regions of Agrelo, Altamira, Lunlunta and Vistalba.

“I do remember walking through vineyards with my grandfather and seeing the large trucks pull in, but it wasn’t really romantic,” says Gabriela, sharing a frank perspective on Argentina’s ‘glory days’ of the 70s, when the country had over 350,000 hectares under vine and per capita consumption was over 90 litres per person.

“Back then, wine production was on a much larger scale, and not as focused on quality. It was a business, not romance. And a business that came once a year… as a young girl I remember having to wait until after harvest to see if I would get that new dress or not! You very much live by the harvest in the wine business.”

The end of the 20th century: a period of transition in Argentine wine

Born in 1968, exactly 100 years after her great-grandfather Angel Furlotti, Gabriela has lived through some major changes in Mendoza’s wine industry: she was born just before the mass production heyday of the early 70s, which came crashing down with the end of the Greco empire in the early 80s.

During the 60s and 70s, a mafioso and ambitious entrepreneur, Héctor Greco, had been steadily buying out the largest wine brands and producers, and gradually monopolising the industry. By the late 70s, Greco controlled 70% of the country’s wine production and was the owner of a large bank. He had actually been using depositors’ savings to finance his own business ventures, a dangerous move which eventually caused the bank to collapse – bringing down his empire and most of the wine industry with him. Thousands of growers were left unpaid and many of the humblest wine families were severely affected.

“I was really young when most of these crises happened, but I do remember all the kids at school talking about Greco when the crisis happened,” recalls Gabriela. “We didn’t even know who Greco was, but everyone was talking about him – it affected almost every family in Mendoza. But the wineries, like my family’s [Furlotti sold most of the business to Greco at the end of the 60s] were the least affected, it was the growers who suffered the most.”

Grape prices dropped by 80% between 1979 and 1982, and bulk wine prices fell from a dollar a litre to two cents a litre. There was a glut of cheap table wine left in the wineries, and no affluent market left to buy it. Few wineries were left unscathed by the crisis, but the brunt of the burnout was borne by the growers, who all of a sudden had no-one to sell their grapes to and no hope of income anytime soon.

The 80s were a painful and isolated period for most of Argentina’s wine producers and growers. The domestic market was shrinking at a rapid rate and showed no signs of recovery. Over a third of Argentina’s vineyards were abandoned or pulled out and by the end of the 80s, there were under 215,000 hectares left.

New beginnings & fourth-generation Gabriela Furtlotti revisits old roots

It was in the following decade that Argentina’s modern wine industry began to take shape. During the 1990s, Argentina entered ‘the Menem era’, during which President Menem pushed through free-market reforms, pegged the Argentine peso as equal to the US dollar and opened up the Argentine economy to the world. New vineyards were being planted and as land was cheap again, there were many foreign investors that came in and an export industry began to grow.

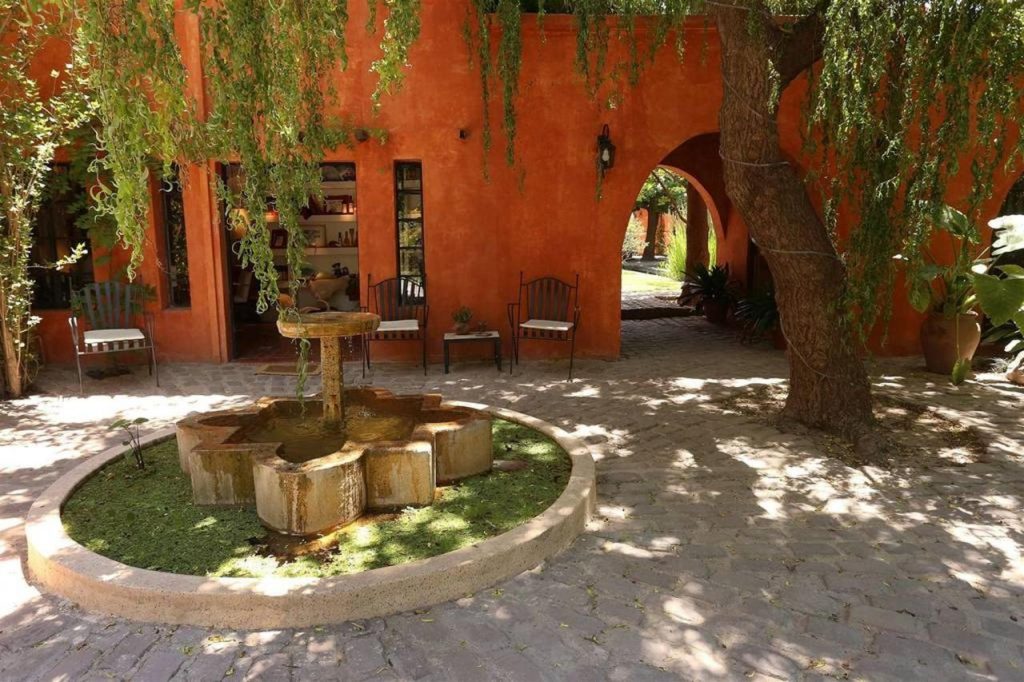

“I wasn’t interested in getting into the wine business like my family had, but it was the only way I could see how to save this beautiful old vineyard!” Gabriela Furlotti explains, waving her hand over the secret garden of old vines that runs alongside the beautiful wine bar and restaurant of Finca Adalgisa. “In 2000, I had to decide what to do with this land – it is my grandmother’s land on my mother’s side [not the Furlotti side] – and so I started to rent rooms in the house.”

“I wasn’t interested in getting into the wine business like my family had, but it was the only way I could see how to save this beautiful old vineyard!” Gabriela Furlotti explains, waving her hand over the secret garden of old vines that runs alongside the beautiful wine bar and restaurant of Finca Adalgisa. “In 2000, I had to decide what to do with this land – it is my grandmother’s land on my mother’s side [not the Furlotti side] – and so I started to rent rooms in the house.”

Finca Adalgisa is one of the few remaining traditional vineyards in Chacras de Coria, which has been overtaken by creeping urbanisation in the last two decades. The vineyard, which was planted in 1916, is predominantly old vine Malbec. “We say it is Malbec but if you walk through my vineyard you’ll find other grape varieties in there. That’s the beauty of old vineyards – the blend is actually made in the field for you. It is probably about 95% Malbec mixed with other grapes, there’s certainly some Barbera, Tempranillo, Cabernet Franc…”

And how many different Malbecs are in there, I ask. “I have no idea! But many. Some bunches are much bigger, or darker, than others. And this natural diversity is what makes old vineyards like this so special. When we harvest everything together, some of the grapes are still quite green, which gives us more acidity, whereas others add more fruit – it all adds to the complexity of the wine, and its uniqueness. It’s a vineyard blend that no-one else has, and that’s why these old vineyards are so distinctive.”

Saving her family’s beautiful old vineyard and this piece of not only her family’s heritage, but Argentina’s tradition and history, was the motive for Furlotti to start a wine B&B, named after the vineyard – Finca Adalgisa. The year 2000 was before any sense of ‘wine tourism’ existed in Mendoza, and Furlotti was one of the first lodgings in Mendoza’s wine regions.

“None of the wineries were even open for tourism then, but I thought that maybe there were some people who would want to stay overnight in Mendoza – although there was no plan to be honest!” Furlotti’s intuition was right, there were some people who wanted to stay in Mendoza, especially in her beautiful family home overlooking an old vineyard.

And as the next financial crisis, that of 2001, hit, suddenly Mendoza became tantalisingly cheap for foreigners to visit. Although it was a time of suffering for many Argentines and local businesses, the wine industry saw the silver lining of the financial crisis – their wines became highly sought after for the quality at such a low price, and wine exports and tourism began to grow.

After a few years of hard graft, Finca Adalgisa began to grow and Gabriela reinvested all the earnings back into the expanding lodge, the vineyard, and renovating not only a winery on the vineyard but one of her family’s (this time the Furlotti side) old wineries in Luján de Cuyo. “The winery is the smallest of the family’s but it is still far too big for me!” she exclaims. “We won’t ever make Furlotti wines of that dimension again – instead I’m renting space to small producers like myself.”

The modern era of Furlotti wine looks back to the very roots of how her family began, with Angel Furlotti as a small contrastista who worked the land and respected the traditions of his Italian ancestors. Gabriela too makes her wines in an artisanal and small-scale way, employing her vineyard workers with a fair-trade system so they too can take pride and ownership in the production. The Familia Furlotti wines take grapes from those same old vineyards that her great-grandfather originally established almost a century ago: in Altamira and Lunlunta.

Her Finca Adalgisa wine remains a field blend of her mixed century-old vines in Chacras de Coria, which are still hand-picked and the ground is still ploughed by horse. The wine rests in the cellar for several years before release, and the result is a wine that is a rich red blend that is both engaging and complex. And if you enjoy drinking it between the vines of Finca Adalgisa with Gabriela Furlotti, as the wine opens up you might just learn something about the liquid history of her family and with it, get an insight into how Mendoza became the wine capital it is today.

Oriundo winery is the boutique project of Oscar Ayestarán and his family in El Hoyo, Chubut, part of the new frontier of Patagonian wine in Argentina. At the foot of Currumahuida mountain, Oriundo wines are influenced by the cool, continental climate of Chubut and their production of early ripening varieties including Pinot Noir, Chardonnay, Sauvignon Blanc, Gewurztraminer and Merlot reflect the cooler Patagonian climate.